NOMADs, NO-ADs, and Us: Why These Biblical Cultures Are Nothing Like Ours.

NOMADs and NO-ADs share deep cultural roots, shaping the world of the Bible and many societies today. So what happens when mobility is no longer a community resource? This blog unpacks the simple difference between these two groups—and why both are radically different from the hyper-individualistic world many of us come from. Discover what we’ve lost, what we can learn, and how to connect deeply with these cultures today.

Nomads: Distinct by Design—What Sets Them Apart and What We Can Learn?

Discover what makes nomads distinct from sedentary cultures, beyond mobility. Explore how their collective identity, traditions, and sense of being “set apart” shape their lives, even across generations. Learn how understanding their distinctiveness can deepen your appreciation of their heritage and faith.

They don’t need you!

Explore the deep value of autonomy in nomadic cultures and its role in survival, identity, and freedom. Learn how nomads balance collective responsibility with independence and how their emphasis on autonomy challenges modern assumptions about freedom and control, offering profound lessons for all of us.

Digital nomads are NOT NOMADs!

Think you’re a nomad because you work from Bali? True NOMADs see mobility as a community lifeline, not a lifestyle. Explore how movement defines survival, identity, and relationships for nomadic cultures, and learn the profound differences between true mobility and modern digital nomadism.

What does Organized by clan look like?

Discover how clan and tribal structures form the backbone of nomadic identity and Biblical community. Explore stories from Scripture and modern nomadic cultures to uncover the value of relational interdependence, mutual responsibility, and how these insights can transform our understanding of family and faith.

What does Networking relationships with outsiders look like?

Discover how nomads naturally network external relationships for survival and flourishing, as seen in Abraham’s alliance with outsider tribes. Explore the relational dynamics of nomadic life, their generational connections, and what we can learn about mutuality, trust, and respect from these ancient practices.

We had no idea how much we needed to know!

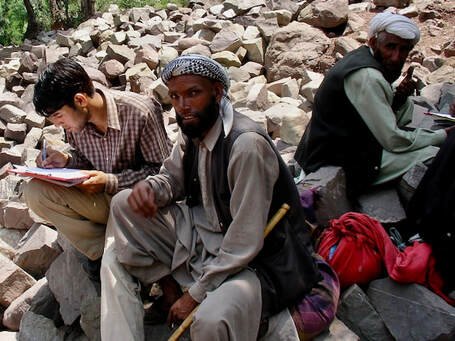

What do you see? A shepherd boy? When presented with a photo like this, we were invited to see the future leader of a nomadic "flock" following the Good Shepherd.