They don’t need you!

Listen: They don't need you!.m4a

Understanding NOMAD Autonomy

Question: Have you ever been in a place where you felt entirely unwelcome—not because of anything you did, but simply because you weren’t ‘one of them’? For NOMADs, this boundary isn’t just about being part of the “in crowd”; it’s a matter of community survival. And the only way to really be an insider is by birth! It has to do with ancestry.

But before we get into the details of autonomy, let’s recap our working definition from my first blog post. NOMADs are Not individualistic, rather the Networking of relationships, both externally and internally, seems built into their DNA. Internally, they’re Organized as clans or tribes. They see Mobility as a resource (even if they don’t appear to use it!) They highly value their group's Autonomy. And they see themselves as Distinct from people with a sedentary heritage.

This week we’re going to unpack the value of Autonomy.

NOMADs highly value their group’s…

Autonomy. As I described in my first post, nomads don’t like outsiders telling them what to do. This can and often does lead to conflict, including with national and regional governments. I can’t over-emphasize the importance of group independence and resistance to outside control. They love their sense of freedom. This will require great sensitivity in your approach to nomads.

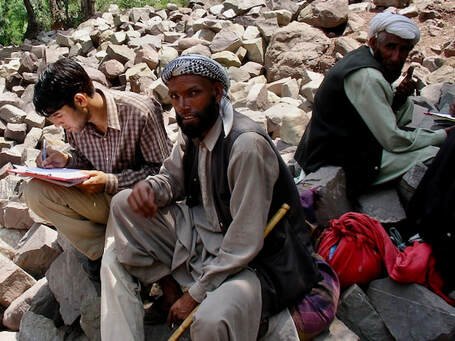

Don’t make my mistake. One spring, an international team of veterinarians came for a visit to our location with some shepherds on migration. One shepherd elder asked in his language, “Mr. Ron, who are these people? And why have they come?” Unthinkingly, I replied, “They have come to teach about best practices in sheep and goat health and breeding.” The elder shepherd retorted, “What do these outsiders have to teach us? At the most, they have been studying this for maybe 40 years. We have been doing it for 4000 years!”

Politically, we think of one state or country governing itself without interference from other states or countries. It sounds scandalous to think of an outside country contributing large sums of money to a political campaign or otherwise trying to influence “our government”. In the same way, nomads and other tribal-oriented peoples take pride in their group’s autonomy, although they may be located under another government’s jurisdiction. In St. Paul, Minnesota, USA, there are large Somali communities who reportedly reject city police interference, claiming “religious freedom” from outside control. However, the issues involved are more about particular Somali customs than Islam. It is more of an “us vs. them” autonomy issue.

Now let me ask, what comes to your mind when you hear the word “autonomy”? Independence? Freedom? Resistance to outside control? Individual nomads do not generally think of themselves as autonomous from their community the way individualistic Americans might. I never asked even my mother and father’s advice in choosing a wife or a place to live. My nomad friends think this is sad and even scandalous! An individual nomad can make independent decisions, but he or she must make those decisions in the context of his or her relationships within the community.

Autonomy intersects with “organized by tribes and clans”. Even among the clans of a single tribe, there are strict boundaries between insiders and outsiders. One shepherd clan camped next to our house for the winter. They protected their goats about to give birth, and those with newborns, in a special enclosure. I had been invited in and was observing and asking questions. When my friend of the same tribe but a different clan arrived for a visit, he came only as far as the gate of the enclosure. I called for him to come in, too. He said, “No, sir. You don’t seem to know our culture. I cannot come in unless I am invited, and I am not even going to ask.” My neighbor confirmed it. He was not about to let someone from another clan come in among his flock. He had his reasons for letting me, a complete foreigner, in but not letting in the man from his tribe but not from his clan.

Autonomy involves mutual commitment over generations. On one level it has to do with a strong sense of mutual responsibility as well as the mutual benefit of being connected to one another. That responsibility is more powerful than the phrase that is expressed in the U.S. Marines, “esprit de corps”, binding former individuals into one body, because the sense of unity goes beyond a lifetime. It defines “us vs. them”, guaranteeing the defense of one another against all external threats, including the extended families of those individuals, from before birth to after death. This is not rugged individualism, but a collective autonomy as a tribe or group.

For whole clans and tribes of Somali, Tuareg, Fulani, Pashtun, and Bedouin, as well as Navajo, Cree, and Dakota tribes, this does not have to be taught or preached. It was already there generations before the person was born and continues long after they are gone. It is endemic, part of their very being for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The time limitation is only based on eras in which, due to internal or external turmoil, pre-existing relationships were dissolved or broken. But then they would be quickly reformed along other lines. It remains for their own group’s mutual protection and provision, two words that form the core of the biblical meaning of בְּרָכָה bᵉrāḵāh “Blessing”!

Why are they like this? Well, think about it. Where do nomads typically live? They live in rugged wilderness areas or on the fringes of sedentary societies. In such environments where survival depends on their own capacity to deal with the harsh realities of terrain, climate, wild animals, and unfriendly neighbors, NOMADs must make their own way, and must not rely on outsiders. Autonomy contributes to how nomads network relationships with outsiders for the good of the tribe. This internal trust and wariness of outsiders also gives them substantial freedom of movement. This contributes to their sense of freedom. They can go, do, and live wherever they want, according to their own needs and opportunities.

Allowing outsiders to dictate their decisions often has negative consequences for nomads, and increases mistrust over generations of experience. I have heard many times about a government that tried to force NOMADs into sedentary housing projects with promises of nice buildings and the amenities of ‘civilized’ life in or close to cities. What did they get? Poorly constructed buildings, water and electric lines that ceased to function soon after the officials left, and lack of access to grazing areas or markets. They lost their livestock or other livelihoods and could not compete for jobs in the city. Even if there were jobs, they were not the types of “opportunities” that nomads have experience with. So now, those nomads are more resistant and distrustful.

Nomad autonomy has its challenges. In episode #2, in talking about networking with outsiders, we saw that this can mean allegiances with certain groups against others. And when war happens in one era, animosity can be carried on so long that few recall why the two groups hate each other. When asked, “Why are you fighting them?” The answer may come back, “Because 500 years ago, they did this to us.”

As outsiders, we need to be careful not to label nomad autonomy as merely “stubbornness.” Rather it contributes to their adaptability in adverse conditions. The high value they place on loyalty and mutual dependence within the group is essential for their survival. This has allowed NOMADs to preserve their culture and identity in ways sedentary groups have not. Even this can lead to conflict with outsiders. Three Biblical examples are: Daniel 3:12 (Jews who refused to worship foreign gods); Ezra 4:13-16 (the Jews were accused of being a rebellious and troublesome people); Esther 3:8-9 (Haman recognized that the Jews had different customs). “Us vs. them” is a two-way street.

So, how does this impact your approach to NOMADs?

First, learn from my early mistakes! Don’t come in as a “rescuer”. NOMADs don’t need you to “fix” them—they’ve survived for millennia without your help.

Start by building trust. Respect their autonomy and show that you understand and value it by becoming their student.

Be a careful and observant listener. Don’t be quick to offer solutions. Ask questions that invite them to share their perspective.

When I translated to the veterinarian the old shepherd’s resistance to teachers, the vet showed me a better attitude. He said, “Tell them, ‘No, actually we didn’t come to teach you. We can see that your animals are quite healthy and reproductive. We want to learn more about your practices so that when we go home or travel elsewhere and see that animals are not doing so well, we can share lessons we’ve learned from you.’ ” This changed everything. And we all went on to learn tremendous things from one another.

How does understanding autonomy help us better engage with NOMADs while also deepening our appreciation for freedom in God’s design?

What can we learn from the NOMAD emphasis on autonomy that challenges our perspectives on freedom and control?

Respect for NOMAD autonomy isn’t just a practical necessity—it’s a recognition of their God-given identity, one that is reflected throughout Scripture.

Share what you’ve learned about NOMAD autonomy with someone today and get their perspective on it. Come back and share it in the comments below.